|

|||||

|

|||||

|

METASPHERE MADE ME ILL TWICE And Other Technical Glitches by JAMES ELLIOTT The Technical Challenges I encountered whilst creating 'Metasphere 1974 + 5' were vast. Many related to the creation of the photo-sculpture itself and these challenges were complex and diverse. Photographically there were also many challenges. The following is really only a précis as an awful lot happens during 332 hours of work. Longer if you include printing the masterpiece. The greatest challenge was the final month of endless sanding, filing and honing of the photo-sculpture, to absolute perfection. Do not mistake this for an abstract arrangement of shapes. It is an absolutely cohesive, seamless and contiguous creation. Although I wore smog masks, the dust inevitably got into my throat and it made me ill twice.

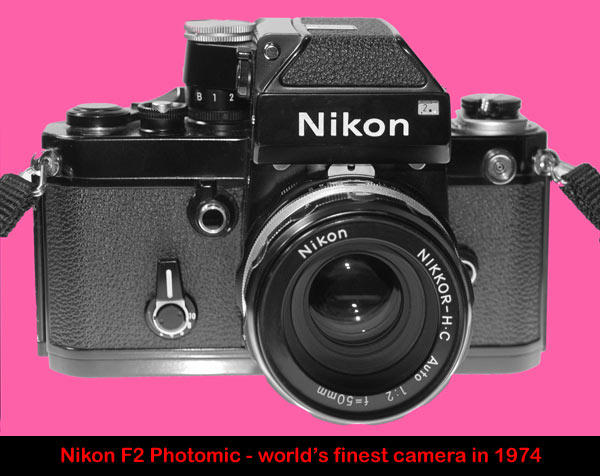

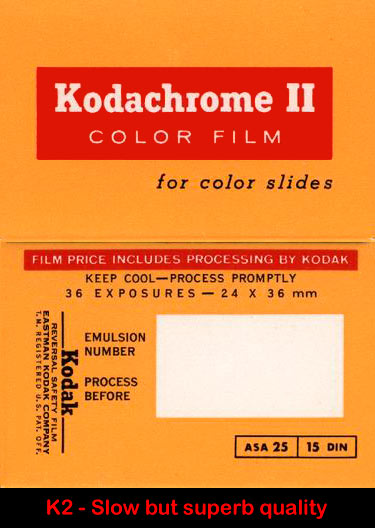

At the time I created it, I was still unable to afford any lighting, so it was all built into the sculpture, including down the tunnel at the back, which would have otherwise been black. I wanted good modelling, but a totally matt, reflection free surface. I used 500 watt photofloods in ordinary sockets, which is not recommended due to the smell of burning bakelite which ultimately, as I discovered, disintegrates. Bakelite was an early, primitive plastic used for light sockets. Such high wattage requires ceramic fittings as I later learned. The photofloods were directed through massive diffusion sheets. Having commenced my masterpiece in November of 1974, I actually shot it in February of 1975, on Kodachrome II, the highest quality film in the world, only available in 35mm format. Early in the 70s I had tested every slide film on the market, about 15 of them as I remember, Kodachrome, Ektachrome, Agfa, Perutz, Anscochrome, Fuji, the list was long. Kodachrome blew everything else out of the water. It wasn't just slightly better, but dramatically so. All colour negative emulsions were drastically inferior to transparency films. I had to shoot Metasphere four times because I kept missing tiny bits of the paintwork and I had to continually make microscopic adjustments to the relative position of the elements. Each time I had to wait 10 days for Kodak to process and return the film, as in the UK they were the only processor of this particular, high quality slide film. Some argued that I could have used large format. This is technical ignorance. Many things are only possible on 35mm and "Metasphere" was certainly one of them. Only this format would yield the depth of field required. As an aside, years later when I created "Superchromatic Spectrosynthesis", I was shooting a subject where the depth of field requirements were considerably less demanding than Metasphere, but although I was only shooting on 6 x 4.5cm film, not large format, it was necessary to remove the lens from my camera and have the internal aperture cam ground down by an engineer, to add an additional two stops to a lens which already stopped down to f22. It was converted to around f45. This was the maximum the internal cam would accept without ruining the lens. The camera technician said to me before he began, "There is a chance I will permanently damage your lens". I replied "Yes I know, but I don't think so, anyway I trust you". He was Japanese - they tend to be good at technical things. Anyway all of this left me in no doubt whatsoever that "Metasphere" would have been impossible, without the use of a 35mm camera.

The film speed of Kodachrome II was 25 ASA (today ISO) and required an exposure of 8 seconds at f16, so a massively robust tripod was required. The colour edition of photographs, I of course printed myself, as I have done with all my work since the beginning. It was an edition of ten. Radically small for an edition at the time but ten has almost become a standard now. I innovated tiny editions, one-offs and unique world editions. Back then editions of 250 or even a thousand were common with other photographers, who saw there work, either as being like a lithograph or intended for publication of some kind. I hated this mass production approach. It seemed to me rather vulgar. What I valued was the individual print, crafted with care by the artist. So my maximum edition was always ten, but I did very few with an edition that large. I think about twenty different images in total, the last one being 'The Inevitability Of Circumstance' of 1987. The Metasphere edition was done on the silver dye-bleach process - known as Cibachrome from 1969 and although later called Ilfochrome, the latter name never stuck and the prints are still universally known as Cibachromes. They are in any case the same process. In the early Sixties there was a version called 'Cilchrome', which required separate red, green and blue exposures for maximum quality, but this was rapidly replaced with a white light version. The name of the process was silver dye bleach. They are often erroneously described as 'dye destruction prints', which just describes what is going on. It's not an official name. It should immediately be noted that only Cibachrome Deluxe had the archival, virtually indestructible polyester base. There was also a resin coated paper version, simply called Cibachrome, which was not considered suitable for archival use by those of a critical disposition, such as myself. It had a lustre finish and so lacked the depth of the high gloss Deluxe Cibachromes, from an aesthetic standpoint. So aesthetics and longevity were two good reasons to choose the Deluxe version, despite its extra cost. My art has always been created regardless of cost. Golden rule. Cibachrome's archival longevity matched dye transfer prints on display and was superior with regards to dark storage, boasting a quoted life span of 500 hundred years. This was the data of the day. People are often surprised to learn that colours can fade in the dark and given that all prints spend a fair bit of their life in said darkness, this is not insignificant. Back in the Seventies and Eighties there were negative films with a rated life of 18 months. Some small formats were so bad, like disc cameras for example, that the exposure required for printing literally faded the negative, so subsequent prints required less exposure as the negative had lost density. Of all printing processes Cibachrome was the central jewel in the crown. Don't listen to what people tell you about dye transfer. I have seen loads of them and to my extremely critical eyes, they are in no way superior to Cibachrome, printed by a master. In fact Cibachrome Deluxe has higher contrast due to the immaculate high gloss finish. If you wanted lower contrast ,one could use silver masking which I mastered. A very meticulous process. Eventually, in the early Eighties a low contrast version of Cibachrome Deluxe was also introduced and this did much to tame the inherently high contrast of the silver dye bleach process. The other thing that worked against dye transfer, was that it was basically a negative positive process and ALL negative emulsions of the day were inferior in quality to the best transparency films. So you were starting of with lower quality. And Cibachrome Deluxe had absolutely fantastic resolution. It could resolve anything you could chuck at it. Hundreds of lines per millimeter. With dye transfer the dyes diffused somewhat. The Cibachrome process basically worked like this. All colour dyes were present in the Cibachrome paper to begin with. This is highly unusual as colour usually comes from the developer via colour couplers. The dyes are arranged in three layers, cyan, magenta and yellow. Each colour also had a corresponding black and white negative layer. A negative image develops in each of three monochrome layers by exposing and processing in a fairly straight forward black and white developer. Bleaching of colour then takes place, with sulphuric acid, in proportion to these three negative mono images.This effectively bleaches out the unrequired portions of the dyes in each layer, leaving a perfect full colour image. As pure azo dyes could be used for this process, unlike the more common papers of the day, vivid images of considerable permanence and quality could be produced.

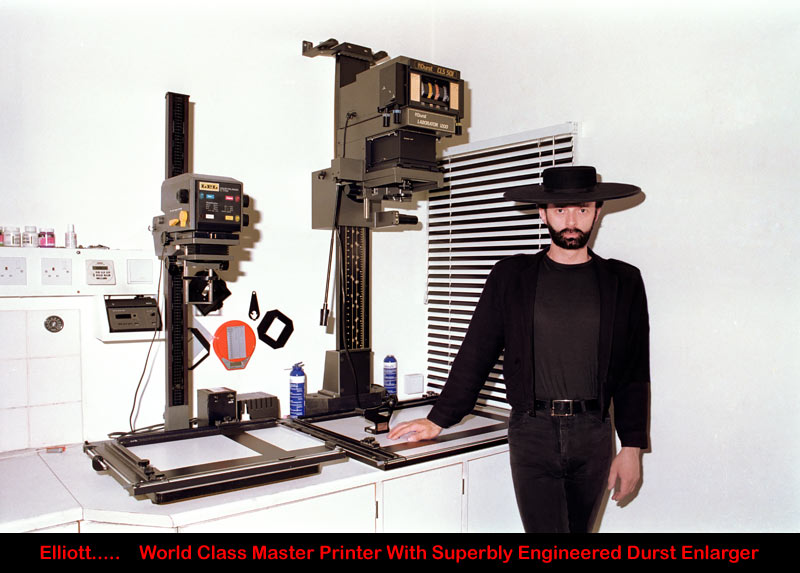

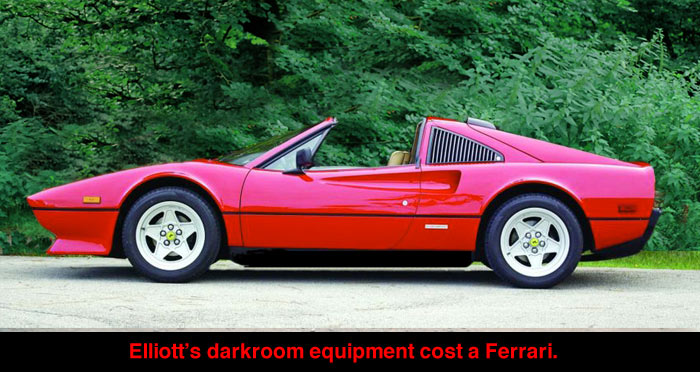

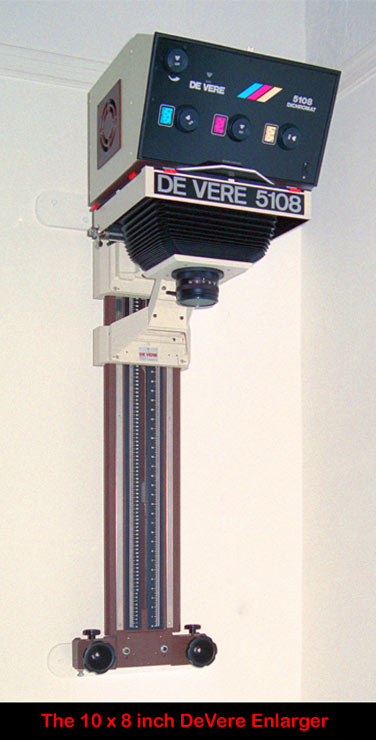

I discovered much to my cost that a very bright enlarger was required, which then presented problems with heat at the negative carrier stage, despite built in heat filters. This caused the negative, or transparency in this case, to move during exposure, as the heat curls it, owing to the different expansion coefficients of emulsion and film base. This, of course, blurs the print. With incandescent light, obviously the brighter it is, the hotter it gets. I discovered that very few enlargers in the world were capable of a very bright light source and a cool negative carrier, despite nearly all enlargers being fitted with heat filters. I was experiencing movement of the film within 20-40 seconds of exposure on most enlargers - easily observable under a micro focus finder. You could literally watch the grain and then the image go out of focus, as the film warmed up. Whilst investigating this, I thought I would test the efficacy of the heat filter in the lamp housing of a very famous brand of enlarger. I fetched my digital thermometer and positioned the probe an inch away from the glass on the cool side of the heat filter. Much to my amazement, within seconds the probe melted and completely ruined my electronic thermometer! How precisely you can call that a heat filter is not clear. This particular famous brand of enlarger, which the managing director of the company assured me was "A standard in every lab in the country", just wasn't up to the job. I told him "I don't care, it is unsuitable for serious work and that is not reflected in its price tag". Around ten times the average weekly wage in the UK. Do the maths. He came over to the Darkstudio and when I demonstrated the problem to him in situ and his conversation started lurching towards "Well.....it's not a perfect world .....is it?!", my eyes glazed over in horror and I knew it was time to wrap it up. To their credit they gave me all my money back. Many famous brands and many arguments with technical teams and managing directors later, I eventually found one capable of critical use. This was the Italian, fabulously engineered, Durst Laborator 1200 enlarger with a CLS 501 colour head. I used three EL-Nikkors with it, lenses made by Nikon specifically for enlarging. I had a 50mm f2.8, a 75mm f4 and a 135mm f5.6, which were for 35mm, 6 x 4.5cm and 5 x 4 inch formats, respectively. They were fabulous lenses, had flat fields and all out resolved even the finest film. Of course one avoided f4 or brighter as depth of focus on the film plane was insufficient and f16 was avoided as exposure was too long and the small aperture caused diffraction to set in, lowering resolution. So one stuck to f5.6, f8 and f11.

From the entire Elliott collection, I have only ever made a total of around thirty or so 36 inch Cibachrome prints. Four of them are Metaspheres and they look magnificent. I only made a small number because printing them is like a nightmare from hell. A piece of dust you can't see, comes out the size of a pea and you can't retouch that. Not on a subject like Metasphere. It has to be clean. So you have to learn about de-ionising film, using compressed air, learning techniques to make invisible dust observable and a ton of other stuff like that which I won't even delve into here, as most of it is incomprehensible, unless you have traveled that route and few people have.

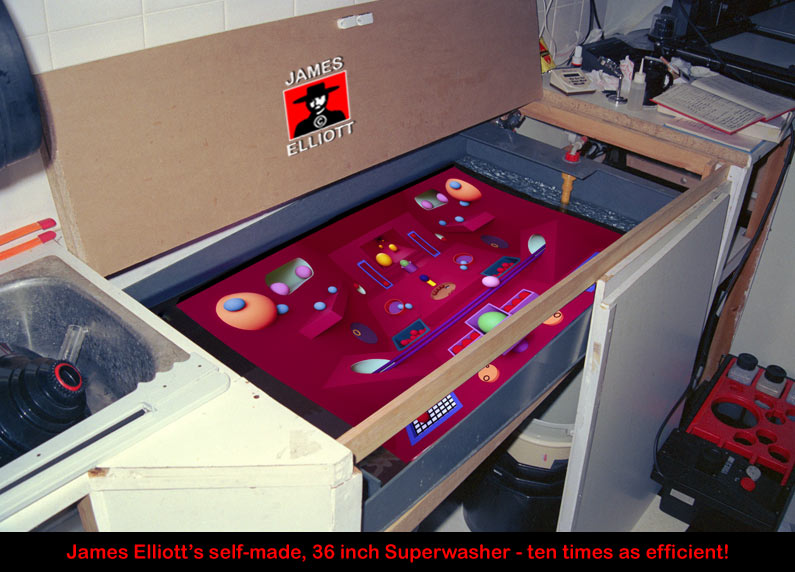

Colour printing is and always has been an inexact science - i.e. one so complex, that if you do the same thing on a different day, the result is different. As for the recommended filtration on colour paper boxes, you could safely ignore those. You can keep notes until hell freezes over - and I did - but you are still guessing every time you print. You just get better at guessing, but many "errors" are always made. Expertise just means your batting average gets better. Each time you hold your breath as you extract the image, still dripping wet with chemistry from the processor. Often you fail, but often you also create something of a quality which is just amazing. The large Metaspheres were created on this self-made machine, which required manual measuring and addition of the chemistry and also manual timing and draining at the end of each step. It yielded breathtaking results.

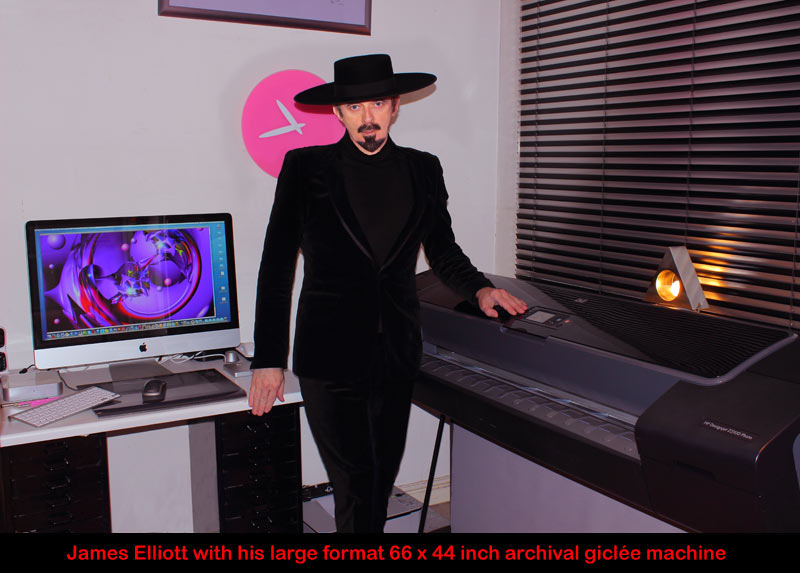

After I wrote this piece, I lost it and found it 20 years later. As it turned out, I never used darkrooms again. Cibachrome was always a high end material and always a costly process vis a vis other papers and chemistry, but it became extremely expensive in the Naughties as labs offering it became scarce. It was then finally discontinued in 2012. One of the longest running print processes ever, spanning 50 years. A testimony to its quality. The advantage of the discontinuation of Cibachrome is that the vintage work becomes impossible to copy or fake. It seals it into a time capsule, as it were. Having watched the development of alternative technology, it was gratifying to see that all the major problems were solved by the turn of the millennium. The quality was there and finally, the permanence problem was solved to a very high degree. Figures of 250 years plus are now quoted for the finest papers and inks, which I use. This is comparable to an oil painting in terms of longevity. That's what I was waiting for. Early giclées, like early colour photography itself, were too imperfect and impermanent for my exacting standards. As the early part of the millennium progressed, the quality of giclées, overtook wet chemistry darkroom prints in quality. So I never returned to darkroom printing, the last prints, a small handfull, being made in 1995. The last marathon, month long session in the Darkstudio in 1992. I went on to master giclée printing, which wasn't too much of a jump from what I already knew. Again I installed my own printers, all of them archival, high end machines, up to 44 inches wide.

Although the colour photographic printing methods I have used over the last 50 years have been challenging and fraught with difficulty, I have no regrets, as historically it has enabled me to print to a standard which would otherwise have been impossible. It helped me create an art of much enhanced power. From the very earliest days people always enquired "Who does your printing?" and many extreme comments were made such as, "The quality just leaps off the walls" or as one put it "Absolutely attacks the senses!". Praise enough to make it all worthwhile and in one's formative years, encouragement matters. As I have commented many times, I no longer care about opinions as I now philosophically understand what they are, and once you do, they become insignificant. Young students find it difficult to understand this strength and sometimes ask if I am feigning indifference. No I am not, I genuinely don't care. I'm the expert around here and I know what I am doing. Only someone unsure of themselves asks for approval. If after 50 years I don't know what I am doing, may the Gods help me! If I had listened to everyone else I would never have colour printed at all, as in 50 years and a lot of photographers later, I never met or heard of anyone who did their own colour darkroom prints. This amazed me. Anyone who has ever heard different renditions of a piece of classical music by different orchestras, will tell you how different they are. Sometimes it is hard to believe it is the same piece of music. Which is correct? Who knows? But you can be sure of one thing. My prints are exactly how they should be. The best they can be both technically and creatively. Technology will change everything now of course, as printing via supreme quality ink jet printers is much simplified and the results magnificent in the right hands. You still need to train your eye to finely tune colour, which takes years, but most of the technical issues outlined here are eliminated. You also need archival expertise and so on, which frankly few people have. I have heard some big name artists say very stupid things in this regard. Computers have their own lexicon of problems, I know, but I nevertheless welcome these fabulous advances in technology, as it means less "fencing with science" and more creativity. Any masterpiece is always a lesser part technique and a greater part creativity. What is astonishing in these times, is that creativity at a certain level is common, but technical mastery, without which creativity is drastically limited, is almost never there. The caveat is that although creativity is the greater part of art, technical mastery exponentially expands creativity and the lack of said technical mastery limits it. Technical inadequacy, which is extremely common, is like driving with the hand brake on. Technical virtuosity is like a creative turbo kicking in. One is a boost, the other is an inertia drag. Digital imaging has revolutionised image creation forever, as has technology in music. People sometimes make fatuous remarks like 'Oh you could do that with a computer nowadays'. Ignorance abounds. Well if you could dream up the original idea in the first place, that would be a start, but that is something uniquely Elliottonian. Sorry, I'm taken. You cannot be me. Anyway, having pioneered cyber art and being an absolute master of it, let me assure you that even if the idea was yours, you cannot create a Metasphere with computers. You could get something close and it would still take a month of Sundays to create, but in the end it would still not quite have the authentic verisimilitude that Metasphere displays. I could do things just as good as that with computers, I have, but not the same. Computers and digital music never made a musician out of anyone and mastering photographic technique won't make an artist out of you, but if you are one, then technology has just thrown you an absolute miracle. Written by James Elliott JAMES ELLIOTT .com © JAMES ELLIOTT 2019 4280 words with 11 illustrations |

|||||